A Pragmaticist Revision of his Conceptions of Interpretation and Criteria

Abstract

In this inquiry I analyse Wittgenstein´s conceptions of use and criteria for the meaning of our language. I interpret his conception of explanation of meaning of a Word in its use in a Language, or teaching someone the use of the words and show that the knowledge of meaning of words must precede their use in language; otherwise, how may the members of the linguistic community know how to use them? Hence, we have to explain how the communal conventions of meanings are established and used. I argue that Wittgenstein´s conception of ostensive teaching of a language is central to acquiring the meaning conventions by the infant on her way to mastering the language. We cannot start our inquiry from the assumption of the already existing communal meaning conventions since the problem is to explain their acquisition and how humans develop and operate their communication. Hence we face a paradox of learning in Wittgenstein´s Investigations since the only possibility of getting word meaning is inside the verbal language-game; but according to Wittgenstein the ostensive teaching for the Meaning of the word cannot be a move in any language-game. The next problem is to understand what the criterion is for learning and using the meaning of the word in the language-game. We face a Fregean difficulty because if the criterion is a private-subjective experience, how do we know that persons experience the same phenomenon and if it is external to the language-game and to our experience, how do we know that our experience represents it truly? My conclusion is that we have to revise Wittgenstein´s Grammatico-Phenomenological conceptions of meaning interpretation and criteria with the Pragmaticist theory of meaning and truth. The criterion of meanings should be the quasi-proof of the truth of their interpretation in propositions, which makes them clear by being true representation of reality.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction: The Problem with Wittgensteins Explanation of Meaning.

- 2. Wittgenstein´s Conception of Explanation of Meaning of Words by their Use.

- 3. Wittgenstein´s Problem with Ostensive Learning.

- 4. Wittgenstein´s “Paradox of Interpretation” and the Meaning of Rules, Words, and Propositions.

- 5. Wittgenstein´s Conceptions of Criteria and Symptoms and how they are Distinguished.

- 6. Conclusion: Pragmaticist Theory of the Truth of Interpretation and Representation.

1. Introduction: The Problem with Wittgensteins Explanation of Meaning.

In this inquiry I analyze Wittgenstein´s conceptions of use and criteria for the meaning of our language. I interpret his conception of explanation of meaning of a word in its use in the language (PI: §43; PI: §49) and show that the knowledge of meaning of words must precede their use in language; otherwise, how may the members of the linguistic community know how to use them (PI §§197-202)? Hence, we have to explain how the communal conventions of meanings are established and used. I argue that Wittgenstein´s conception of ostensive teaching of a language is central to the infant´s acquisition of meaning conventions on her way to mastering the language (BB:17, PI: §§27-49). We cannot start our inquiry assuming the already existing communal meaning conventions because the problem is to explain their acquisition and how humans develop and operate their social communication (Bloor, 1997; Habermas, 1998). Hence, we face a paradox of learning in Wittgenstein´s Investigations: the only possibility of acquiring word meaning is inside the verbal language-game, yet the ostensive teaching for the Meaning of the word cannot be a move in any language-game. Consequently, the infant cannot learn the word meaning either inside or outside a language-game. Therefore, in Wittgenstein's Grammatical Philosophy we cannot explain how language is learned and taught: either we already know mysteriously the language-games or we can never know them (Plato, Meno:80e).

The next problem is to understand what the criterion is for learning and using the meaning of the word in the language-game. We face a Fregean difficulty because if the criterion is a private-subjective experience, how do we know that different persons experience the same phenomenon, and if the criterion is external to the language-game and to our experience, how do we know that our experience represents it truly? Wittgenstein´s device to maintain his conception of meanings in the language-game is similar to Frege´s conception of objective Platonic thoughts, while Wittgenstein replaces them by his communal conventions, which come from nowhere (Nesher, 1987, 2002:X).

My conclusion is that we have to revise Wittgenstein´s Grammatico-Phenomenological conception of criteria within the Pragmaticist theory of meaning and truth. The criterion of meanings should be the proof or nonverbal perceptual quasi-proof of the truth of their interpretation in propositions, which makes them clear by being true representation of reality (Nesher, 2002, 2004).

2. Wittgenstein´s Conception of Explanation of Meaning of Words by their Use.

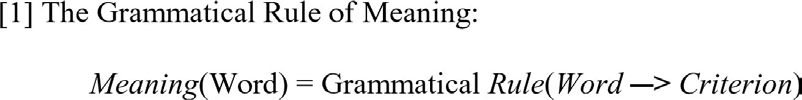

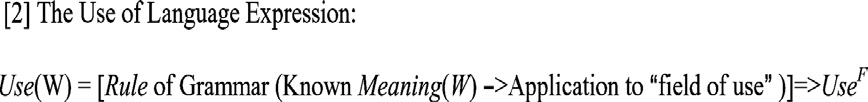

According to Wittgenstein the meaning of the word is given by the grammatical rule of a language-game which connects a word with a specific criterion for its meaning in the language-game. Following the grammatical rule of meaning is performed according to our conventions about how to use this specific word in a proposition while asserting it in the language-game (Hintikka, 1986:201ff.).

According to Wittgenstein we can learn the meaning of a word either inside the language when someone explains a word for us by using other words whose meanings we already know, or by ostensive teaching, when someone shows us an object outside the language that the word is about. When Wittgenstein says ”Let the use teach you the meaning” (PI: §212) he means that we can learn the rule of meaning of the word from the use of the word by others who already know its meaning. This use is the criterion for learning the rule of meaning and we cannot identify the meaning itself with the use, as some suggest (Nesher, 1992). To describe our use of the verbal language, Wittgenstein extended the framework of language to what he calls the language‑game. This extension includes nonverbal activities, tools, samples, and objects, i.e., ”the field of use of the expression” (Malcolm, 1958:50), pertaining to the operations of the language itself (PG §29; P I §§6, 7, 16, 23, 50).

Accordingly, to know how to use a word is to know the rule of grammar operating the word with its known meaning, and applying it in the specific field of use (UseF) of the language-game. The knowledge of word meaning must precede its use and only in ostensive teaching of words to an infant does she first learn the meanings of rules and words. Thereby we can see clearly how one can learn a verbal language without knowing any implicit conventions about the meanings of its expressions.

3. Wittgenstein´s Problem with Ostensive Learning.

The predicament of ostensive teaching is that if it is a language-game then how the infant learns such a language-game without knowing any verbal language. Clearly, she learns the first conventions of a language-game instinctively and practically outside any verbal language-game, and she must learn it with her private pre-verbal language. According to Wittgenstein, however, without public criteria there cannot be any objective understanding of meanings of rules and words. This is probably the reason why Wittgenstein tries to avoid calling ostensive teaching a language-game and regards it only as a preparation for the language-games.

We may say: nothing has so far been done, when a thing has been named. It has not even got a name except in the language-game. This is what Frege meant too, when he said that a word had meaning only as a part of a sentence. (PI §49)

We can see how Wittgenstein´s problem with the ostensive teaching is connected to his rejection of the conception of private language (PI:174ff., 378ff.; BB:3-4). This paradoxical situation about how an infant learns the meaning of the first words in language can be due to Wittgenstein restricting the conception of learning to the verbal language alone. Consequently one has to learn verbal language meanings in a language-game one does not yet know; therefore, it is impossible to learn verbal-language, and with non-verbal language there cannot be any certain communication (PI: §202). Hence, the infant learns her first language-game with pre-verbal cognitive communication. Similarly we can explain the entire development of the language-game, how humans start to use language.

Our language-game is an extension of primitive behavior. (Z §545)

But what is the word “primitive” meant to say here? Presumably that this sort of behavior is pre-linguistic: that a language-game is based on it, that it is the prototype of a way of thinking and not the result of thought. (Z §541)

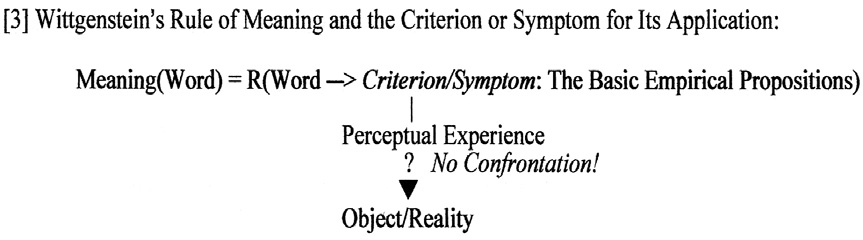

The explanation of the ostensive teaching must start from the instinctive and practical components of our perceptual operation and how they represent external reality and terminate in true judgments. This is Wittgenstein´s difficulty with the relation of the basic empirical propositions to external reality. According to his Grammatico-Phenomenology, our “picture of the world” is the “reality” against which we evaluate other propositions (OC §§94f.; PI §§354-5).

The propositions describing this world-picture might be part of a kind of mythology. (OC §95)

If the truth is what is grounded, then the ground is not true, nor yet false. (OC §205)

However, the criteria for meaning and truth are both in the system of language-games and constitute its foundations (OC §§80ff.). For Wittgenstein, the ostensive definition is problematic as a move to establishing meaning because it does not have the certainty he claims grammatical rules to have (PI §§31ff.). For him only rational justification inside the language-game can be certain, and such justification is based on already accepted empirical propositions of our inherited background. Yet this relation of linguistic expressions to their meaning criteria is the most primitive and genuine grammatical relation: without it the grammatical rules in the language cannot be established.

4. Wittgenstein´s “Paradox of Interpretation” and the Meaning of Rules, Words, and Propositions.

In his discussion on the interpretation of meaning of rules Wittgenstein shows that under some understanding of interpretation we arrive to a paradox about following rules.

But how can a rule shew me what I have to do with at this point? Whatever I do is, on some interpretation, in accord with the rule.”--not what we ought to say, but rather: any interpretation still hangs in the air along with what it interprets, and cannot give it any support. Interpretations by themselves do not determine meaning. (PI:§198)

This is the case with Wittgenstein´s kind of hermeneutic conception of interpretation.

This was our paradox: no course of action could be determined by a rule, because every course of action can be made out to accord with the rule. The answer was: if everything can be made out to accord with the rules, then it can also be made out to conflict with it. And so there would be neither accord nor conflict here.

It can be seen that there is a misunderstanding here from the mere fact that in the course of our argument we give one interpretation after another; as if each one contented us at least for a moment, until we thought of yet another standing behind it. What this shows is that there is a way of grasping a rule which is not an interpretation, but which is exhibited in what we call “obeying the rule” and “going against it” in actual cases.

Hence there is an inclination to say: every action according to the rule is an interpretation. But we are to restrict the term “interpretation” to the substitution of one expression of the rule for another. (PI:§201)

I argue that Wittgenstein´s “Paradox of Interpretation”, as I call it, comes from a wrong conception of Interpretation, like the “liar paradox” which comes from a wrong conception of truth (Nesher, 1997). Wittgenstein´s conception of Interpretation is of endless operations in which we replace “one interpretation after another.” The epistemological base of this conception of interpretation is Wittgenstein´s Phenomenological conception of language-game, neither inside nor outside of which can we reach any confrontation with reality (PG: §68). Yet only by such confrontation we can prove the truth of our interpretation without continuing it endlessly. But without such proof “Interpretations by themselves do not determine meaning.” Due to this paradoxical situation, Wittgenstein rejects Interpretation as a way of understanding the meanings of expressions (Baker & Hacker, 1984:19).

To overcome the “paradox of interpretation” Wittgenstein had to invent a mysterious conception of “grasping a rule which is not an interpretation” (PI: §201). Without having any epistemological explanation of how we learn the rules, understanding them and controlling their use, we cannot distinguish between “`obeying the rule´ and `going against the rule´ in actual cases”, which is only a description of a behavior in respect to already established conventions. Therefore, we have to accomplish a radical revision of the epistemology of our acquiring the meaning and the truths of our cognitions (Tarski, 1969; Nesher, 2002). I suggest moving from the premisses of Wittgenstein´s grammatico-phenomenological conception of knowledge of meanings to Pragmaticist realism, to understand the criterion not as the phenomenon but as the proof of the truth of the interpretation of the meanings of our cognitive signs to “make our ideas clear”, to know their meanings.

5. Wittgenstein´s Conceptions of Criteria and Symptoms and how they are Distinguished.

Without Wittgenstein´s mysterious “grasping”, what are the criteria for the pre-verbal behavior for creating and learning new conventions of a verbal language-game? According to Wittgenstein, the tacit presuppositions of our language-games are our basic empirical propositions, the basic “descriptions” of our form of life activities. These are the indubitable criteria, our norms against which we measure the truth and falsity of other propositions, the meanings of their words, and our right or wrong behavior in following the rules of our language-games (OC: §§94ff.). But how we acquire these criteria and how is the conception of the criteria distinct from the conception of symptoms? Some interpreters suggest that the distinction is not comprehensive and systematic because it follows a variety of the ordinary language usages of these terms. Wittgenstein suggests a relative distinction between criteria and symptoms because it is not clear how the normative criterial justifications of meaning and truth differ from the empirical inductive logic of symptoms (BB:24-25, 51, PI: §§322ff., 354f.). The distinction between criteria and symptoms seems to be between the grammar of conventions and the sense-impressions experience by which we acquire the former (OC: §§94ff.). Our basic propositions are our basic conventions but as such cannot be derived from other conventions, and since they are not just arbitrary propositions, they must be somehow proved to be true representation of our reality. Without confrontation of the language-game system with reality through the sense-impressions experience, our common-sense world-picture will remain only mythology without any explanation of the development of our form of life through replacement of the norms of one language-game by the norms of a new one (OC:§94ff.). But Wittgenstein, in his Grammatico-Phenomenological Investigations, cannot explain such confrontation with reality.

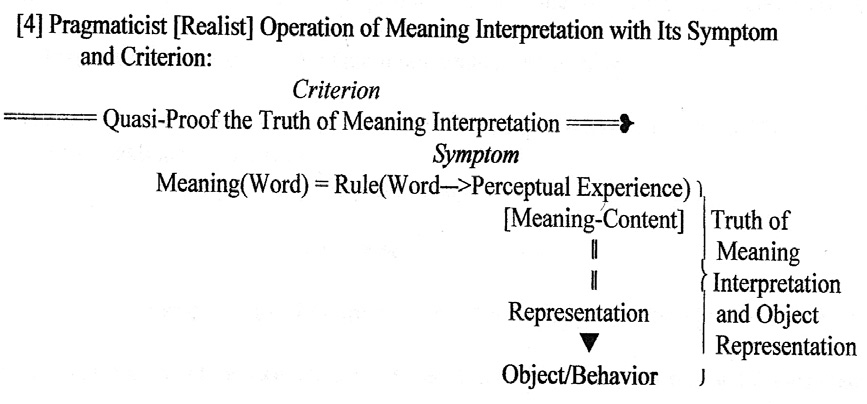

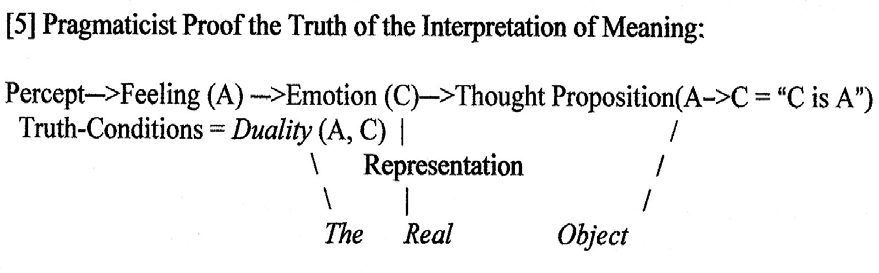

What is the Criterion by which we “explain” or ”define” the Meaning of the Word? Some Wittgensteinians call the explanation of the nature of the criteria for the meanings of the rules and words in the language-game “criterial semantics”, as distinct from “truth-conditions semantics.” What is the nature of this Criterion? Is it for the meaning of the word or for the truth of the ostensive teaching, or for both? According to Wittgenstein it is for the meaning of the word, but since the first basic words can be learned only in the ostensive teaching how a private experiential phenomenon can be an objective criterion for the meaning of its name? Therefore, the true perceptual representation of the name's object is constitutive for the criterion in the ostensive teaching. The Meaning of the word and the Truth of the ostensive teaching are connected, and without them the entire move cannot work. Wittgenstein's epistemological problem lies in his severing the connection between the interpretation of cognitive meanings inside the language and the representation of reality outside it. This must lead to an endless series of interpreting criteria and to the impossibility of representing reality. The question is whether Wittgenstein can explain the meaning of our language without connecting the experiential meaning-content and the truth of such experience. The experience of the feeling of meaning can only be the symptom of understanding the meaning of the word, and not its criterion, if it has to be a conventional norm and therefore certain. The symptom as feeling the meaning of a word is one´s reflection on the relation between the word and the meaning-content of experiencing an object. If the feeling of meaning of a word is only the symptom of understanding its initial-vague meaning, how may we establish it as clear meaning? The criterion for such meaning cannot be any phenomenal experience or external object but rather the quasi-proof of the truth of our interpretation of the initial-vague meanings of the components of the perceptual judgment. The conception of quasi-proof, which I developed from the Peircean cognitive semiosis, is the perceptual instinctive self-controlled proof of our perceptual judgments (Nesher, 2002). The following is a Pragmaticist-Realist reconstruction and an alternative to Wittgenstein´s rule of meaning in ostensive teaching.

Here the symptom is the Feeling of initial-vague Meaning-Content of one Perceptual Experience with Object/Behavior. The criterion is the quasi-proof of thetruth of the Interpretation of theinitial-vague meanings synthesized in the Perceptual Judgment Representing the real Object/Behavior. Hence, the feeling of ”wet and cold” is only a Symptom of experiencing rain, the initial-vague feeling of Meaning-Content which without the proof the truth of its interpretation is still doubtful (PI: §354). This is distinguished from the Wittgensteinian conception of the criteria as phenomena which belong to the grammar of language-game without being proved a true representation of external reality, and which thus can be defeasible (McDowell, 1983:369ff.). This Pragmaticist epistemology of the Criterion as the Quasi-Proof of the Truth of the Interpretation of Meaning is not thetruth-conditional conception of meaning. It is not the truth-conditions that determine the meaning of the Word but the criterial proof upon the truth-conditions, which are components of the proof operation (Nesher, 2002).

6. Conclusion: Pragmaticist Theory of the Truth of Interpretation and Representation.

My conclusion is that with the Pragmaticist theory of meaning interpretation and the proof of its truth, we also prove our knowledge of reality. These proved true cognitions are the communal conventions of our form of life. The problem of Wittgenstein´s two philosophical perspectives is that neither the Tractarian formal semantic model nor the grammatico-phenomenological Investigations can explain human cognitive behavior and its meaning and truth. Thus neither Analytic Philosophy nor Philosophical-Phenomenology can explain our representation of the reality in which humans operate and develop their lives (Nesher, 2004). The pragmaticist revision of Wittgenstein´s conception of criterion is also a solution to the Fregean Puzzle of “compositionality” and the “hermeneutical circle” paradox.

We begin our perceptual operation from the initial-vague cognitive meanings of Feeling A and Emotion C as experiences of the Real Object. If there is a Coherence between A and C then their Interpretation in the proposition A–>C is proven a true representation of the same Real Object. Therefore, the Interpretations of A and C are True and their Meanings are certainly clear as components of true A–>C being true representation of the real object. This can be seen as a solution to the Fregean “compositionality” and the “hermeneutical circle” that through reflective control over a complete proof, not a formal proof but the Peircean trio sequence of Abduction, Deduction, and Induction, we can avoid any vicious circle or an infinite regress (Nesher, 2002). We do not prove the truth of the meanings of the proposition’s components but the truth of their interpretation-synthesis in the proposition itself. We prove the interpretation because every proof is an interpretation of the assumptions and every complete proof is a true interpretation.

This is not a sort of Verificationist Theory of Meaning since the proof of the truth of the proposition “C is A” only makes certainly clear the meanings of its initial-vague components A and C. According to the Logical Positivist Verifiability Principle of Meaning a proposition is meaningful if, at least in principle, it can be verified or falsified in the formal semantics. This Verificationist principle has the function of eliminating metaphysical propositions that are meaningless because they are unprovable as true or false. According to my pragmaticist theory of meaning and truth every human experience has some initial-vague meanings and in the interpretation we can make the meaning-ideas clear and distinct representation of reality. Metaphysical propositions also have experiential meaning-contents as our utmost empirical generalizations, but in distinction from Kant and the contemporary neo-Kantians, e.g., Putnam, we can evaluate them empirically. If such propositions have not been proven true or false they remain doubtful, but a doubtful proposition is meaningful though it is still vague. Thus I reconstruct Wittgenstein´s conceptions of meaning and criterion with the Pragmaticist theory of meaning and truth.

Literature

- Baker, G.P., & P.M.S. Hacker 1984Scepticism, Rules & Language. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Bloor, D. 1997 Wittgenstein, Rules and Institutions. London: Routledge.

- Habermas, J. 1998 On the Pragmatics of Communication. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

- Hintikka, M. & J. 1986 Investigating Wittgenstein. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Malcolm, N. 1958 Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- McDowell, J. 1983 “Criteria, Defeasibility, and Knowledge.” Reprinted in his Meaning, Knowledge, and Reality. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1998.

- Nesher, D. 1987 “Is it really that `the thing in the box has no place in the language‑game at all´ (PI#293)? A Pragmatist Alternative to Wittgenstein and Putnam´s Rejection of Mental Meaning.” The 12th International Wittgenstein Symposium, Kirchberg, Austria Aug. 1987.

- ________ 1992 “Wittgenstein on Language, Meaning, and Use. “ International Philosophical Quarterly Vol. 32 No. 1, March 1992:55-78.

- ________ 1997 “The Pragmaticist Conception of Truth and a ‘`Bold´ Solution to the Liar Paradox.” Read at the 20th International Wittgenstein Symposium, Kirchberg, Austria, August 1997.

- ________ 2002 On Truth and the Representation of Reality. University Press of America.

- ________ 2004 “Meaning as True Interpretation of Cognitive Signs.” Read at the conference On Meaning, Haifa University, Dec. 2004.

- Tarski, A. 1969 “Proof and Truth.” Scientific American, 220 (June)1969:63-77.

- Wittgenstein, L. 1953Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1969 (PI).

- ____________ 1958The Blue and The Brown Books, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1958 (BB).

- ____________ 1967Zettle, Berkeley: Univesity of California Press, 1970 (Z).

- ____________ 1969On Certainty, Oxford: Basil Blackwell (OC).

- ____________ 1974Philosophical Grammar, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, (PG).

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.