Abstract

In the context of a cooperative project ("Culture and Value Revisited") between the Brenner Archives at the University of Innsbruck (FIBA) and the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen (WAB), a computer supported qualitative analysis of Wittgensteins "Vermischte Bemerkungen" / "Culture and Value" is being carried out. This is done with GABEK (Ganzheitliche Bewältigung von Komplexität, Holistic Processing of Complexity), a method based on the theory of linguistic Gestalten (Zelger 1999) and its computer implementation WinRelan. With GABEK the essential aim is to obtain a holistic, integrated view of individual aspects of Wittgenstein’s remarks in Culture and Value (1994 Suhrkamp edition).

The GABEK method for qualitatively analysing data allows a hierarchically structured presentation of a highly complex text and its network layers. The main objective of this analysis is to clarify and highlight content-related (semantic) interdependencies and intervening variables - hypotheses on inter-dependencies can be generated in a further step.

Development of a rule-based network of data leads to the generation of

- -conceptual fields

- causal interrelations of items (keywords),

- conceptual fields and topics

- semantic inter-dependencies and networks

the analysis and identification of which are needed to generate both deeper knowledge and understanding about the semantic structures of the Wittgenstein text.

This knowledge expresses itself in the unique character of its organisation and structure and could help build the basis for further in-depth exploration and analysis concerning specific topics related to "Culture and Value". Consistent with the core objectives of the analysis of the German text version ("Vermischte Bemerkungen"), an encoding of the 1st and 2nd English edition ("Culture and Value") will be done for the purpose of comparison and exploration in terms of textual semantic similarity and deviation. These findings will provide the basis for further investigations concerning such questions as: What kind of text is this? Is the secret code in Wittgenstein’s remarks of any significance? Is there a Wittgensteinian philosophy of culture found in the patterns and networks identified?

Table of contents

- 1. Introductory remarks

- 2. What a text analysis can do

- 3. Applying GABEK/ WinRelan to the Vermischte Bemerkungen

Proceeding developments in digital humanities and ques-tions concerning the constitution and textual organisation of Wittgenstein’s Vermischte Bemerkungen suggested the venture to apply GABEK/WinRelan®1, a multi-methodological oriented text-analysis tool, to these re-marks. This paper introduces the technical terminology as well as some important aspects of the working process necessary for an understanding of the retrieval of semantic fields and structures within the Vermischte Bemerkungen.

1. Introductory remarks

In the context of the cooperative project (FWF Culture and Value Revisited) between the Brenner-Archives at the University of Innsbruck (FIBA) and the Wittgenstein Archives at the University of Bergen (WAB) a computer supported qualitative analysis of the Vermischte Bemerkungen is being carried out. This is done with GABEK (Ganzheitliche Bewältigung von Komplexität, Holistic Processing of Complexity), a method based on the theory of linguistic gestalten (Zelger 1999), and its computer implementation WinRelan (Windows Relationen Analyse. By a content/semantic analysis of the material an integrated view of individual aspects of Wittgenstein’s originally scattered and often private notes and remarks on various topics, which were assembled, edited and published by von Wright (1994) in Culture & Value could be obtained. It is the project’s basic intention to look to investigate philosophically relevant semantic fields (patterns) within the remarks from which we could then gain semanitc knots acting as thematic ancors for further investigations in BW and BEE.

2. What a text analysis can do

Georg Henrik von Wright still saw himself faced with the problem of the arrangement of the numerous notes and scattered among the philosophical and biographical texts Wittgenstein had left. In his foreword to the first edition of Culture & Value (1977) von Wright wrote:

It was a decidedly difficult task; at various times I had different ideas about how best to accomplish [the selection and arrangement of these remarks]. To begin with, for example, I imagined that the remarks could be arranged according to the topics of which they treated -such as "music", "architecture", “Shakespeare", "aphorisms of practical wisdom", "philosophy", and the like. Sometimes the remarks can be arranged into such groupings without strain, but by and large, splitting up the material in this way would probably give an impression of artificiality. (von Wright 1977, ix)

In some cases it seems difficult to decide what Wittgenstein was referring to and therefore any kind of classification or attribution to certain topics only by reading through these notes would lack any rule- or criteria-based structure. This is now where computer based text analysis comes into play. A text analysis tool can be used to identify the context and importance of text without the intervention of the researcher. Thus, we try to investigate any inherent semantical and topical structure of this seemingly loose collection applying clear and transparent criteria. We are not primarily interested in analyzing the circumstances under which the Vermischte Bemerkungen were written and later combined. The texts themselves will be our first and only fields of investigation – at least at this stage. Despite being a loose collection, the textual analysis of these remarks assembled in Culture & Value could result in something like topical signposts hinting at recurrent themes in Wittgenstein’s corpus. In this way we could gain access to clusters in the corpus which may be indicative of philosophical topoi hitherto uninvestigated as such. Thus, once a first analysis will have been completed, framing and re-framing into the larger context of text genesis as well as Wittgenstein’s writings and letters should follow.

With Wittgenstein’s works in general and with the Vermischte Bemerkungen in particular the question is again one of textuality. The question what constitutes a text (by Wittgenstein), is becoming even more virulent with the Vermischte Bemerkungen since the text itself was not arranged by Wittgenstein but edited posthumously. The problem, now, is to locate this text’s (or rather these text units’) central cores holding the essentials of its meaning(s). Before any attempt at an interpretation of this text can be made, the semantic “hot spots” have to be identified. Once uncovered, what we would get are various semantic fields and meaning-structure(s). Frequency as well as the degree of cross-references between different semantic fields may indicate probable semantic and thematic “centers of gravity”. Thus, what a semantic text analysis can do, is looking for a "textual architecture" and trying to hint at crucial text criteria such as cohesion, coherence, intratextuality and – to some extent – intertextuality within Vermischte Bemerkungen. So we could finally reveal one or more thematic “red threads” and the an arrangement of the remarks according to various topics would no longer be artificial or at random.

Any interpretation of the text arises in that the topical building blocks (semantical fields) are understood as the meaning-structure(s) of the text. Metaphorically speaking, every text consists of various houses and its inhabitants performing with inhabitants of other houses contained within a certain text. Each of them is of different importance in the structure of the text. However, content analysis applies a set of techniques to a given text to determine the following:

- * the identity of the main houses and inhabitants (semantic keywords and fields),

- * the relations in which they stand to each other (constituting semantic networks),

- * the hierarchy of these relations and how they evolve (forming the textual framework).

Content analysis consists in revealing the foci within a certain text, i.e. its meaning. This necessarily implies two things. First, there must be a theoretical conception of the text describing both the textual organization of the things said as well as the structural organization of the thought-processes of the author. In case of the Vermischte Bemerkungen both can best be done by rule-based text-coding. Since the actual version we have is a mere construct, the question is if the various text fragments may hint at a larger underlying textual (and philosophical) conception or “hypertext”, which would finally legitimate the appliance of the concept of “text” to the Vermischte Bemerkungen. Secondly, this implies the use of a tool which rigorously tries to exclude the subjectivity of the investigator to a maximum extent.

3. Applying GABEK/ WinRelan to the Vermischte Bemerkungen

The advantage in using the GABEK/ WinRelan method lies within the fact that it allows a hierarchically structured presentation of a highly complex text and its network layers. The main objective of this analysis is to clarify and highlight content-related (semantic) interdependencies and intervening variables – hypotheses on inter-dependencies can be generated in a further step. Whereas other semantic text analysis tools are designed to help the researcher identifying particular components of natural language (morphemes, words, syntax, semantics etc) and calls upon a number of pre-defined rules, GABEK is a method in which themes (or classes of concepts) as well as causal interrelations among themes are encoded. The method involves a three step encoding process.

3.1 The encoding process

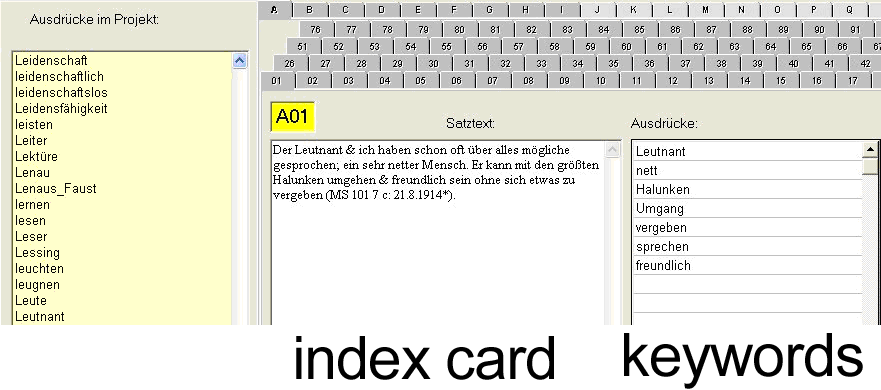

When using WinRelan the first step is to divide the text up into chunks, which are then transferred onto so called index cards (see Fig. 1). Each card should include a semantically closed statement2 whereby the length of text units represented on these cards is determined by the number of keywords. Keywords are words that constitute the semantic content of a text and are – in general – easily identified.

Fig. 1: Index card and corresponding keywords

Fig. 1: Index card and corresponding keywords

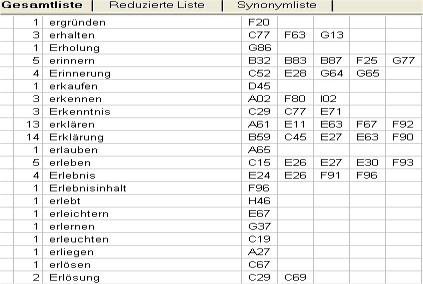

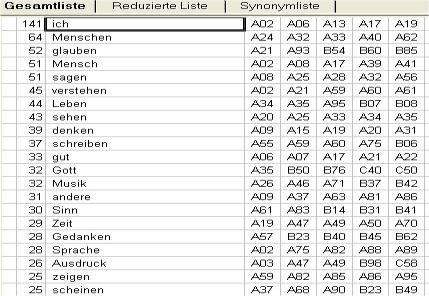

What we finally get is a kind of concordance, so we can, for instance, list all words in alphabetical order (see Fig.2) which are repeated in the text two or more times, or create a chart showing the words in the text ranked in order of their frequency of occurrence (see Fig.3).

Fig. 2: Keyword list in alphabetical order

Fig. 2: Keyword list in alphabetical order

Fig. 3: Keyword list according to frequency

Fig. 3: Keyword list according to frequency

Both lists derive their power for analysis from the fact that they allow us to see every place in a text where a particular word is used and therefore helps the researcher to anticipate relevant semantic fields for a subsequent detailed analysis.

As a rule one would have between three to nine keywords on each index card3, which would mean approximately three sentences. As GABEK/WinRelan is mainly used for analyzing spoken text data, the keywording and coding of Wittgenstein’s dense and highly complex remarks turns out to be quite a challenge. Where one would normally have several sentences on one index card, with Wittgenstein it is often necessary to have only one or two sentences on one card. As long as we are merely aiming at an identification of keywords in order to compile a keyword list (e.g. for a concordance or register), showing the frequency in usage of specific terms, this is fine. However, it is essential to follow the rules in regard to further data processing. Now this is where WinRelan meets its limits. Especially when it later comes to building linguistic gestalten, i.e. doing a strictly rule-based summary of the contents of those index cards sharing again five to nine keywords, index cards with too many sentences and equal or different keywords respectively will turn out to be useless. Why? This has to do with the algorithm used for the virtual grouping of semantically fitting index cards.

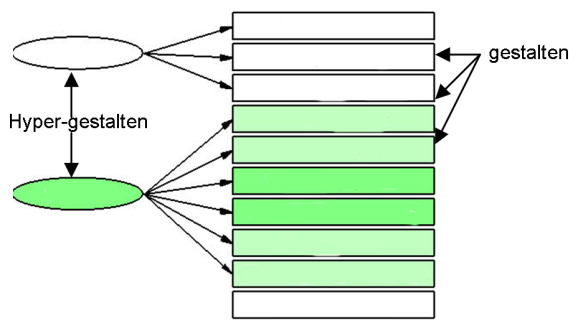

After all index cards have been coded, they have to be arranged into groups. This is done by running a cluster analysis on all keywords identified at least twice on at best five to nine index cards. The cluster analysis is a built-in feature (in WinRelan) and helps the researcher to generate virtual piles of index cards sharing again five to nine keywords. However, if there are too many index cards with too many different keywords (cf. Zelger 1996, 11), one would get too many groups i.e. too many topical threads so that an identification of more and less prominent themes would be impossible. On the other hand, if the index cards share too many keywords, we would get too few piles and it would seem as if all topics were equally prominent; either is problematic. Because when it comes to summarizing the content represented on these grouped cards according to specific syntactic and semantic rules, we would either get a too comprehensive summary or only a superficial one. The summaries (gestalten) are semantic implications of the grouped cards and build the basis for further grouping and summarizing on the next higher level. What we get are so called hyper-gestalten. This process is repeated until we have no more groups to summarize. The final product is a gestalten-tree any careless or deviant coding at an earlier stage affects the quality of the later analysis.

Fig. 4: Gestalten-tree

Fig. 4: Gestalten-tree

Thus, the decision on how many sentences are to be coded on one index card is a crucial one.

Apart from the process of coding and clustering, the positive or negative evaluation of the keywords as well as the causal coding are important to a comprehensive text analysis, in a second step. Causal coding allows researchers to identify causal relation between keywords. Consequently, two lists are generated: the “causal list” and the “list of causal relations”. Whereas, the causal lists provides information on the amount of causal effects between keywords, the list of causal relations shows more about the nature of these interdependencies.

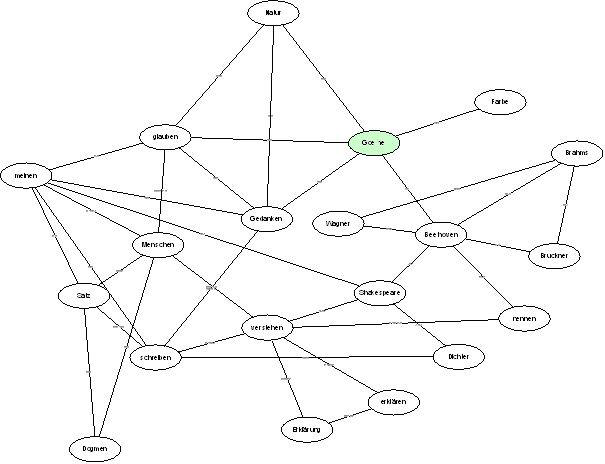

Although there are other features relevant to a comprehensive data analysis, we will only go into one more important detail for reasons of comprehensibility. The third step important for our investigations is the generating of causal network graphics, which are based on the coding of causal relations. The researcher may, for instance, choose any keyword from the keyword list and can create a network by expanding it with keywords that shows at least two interrelations with the starting keyword. Let take the following example, starting with the keyword “Goethe”:

Fig. 5: Causal network graphic starting with “Goethe” (marked green)

Fig. 5: Causal network graphic starting with “Goethe” (marked green)

The analysis and identification of causal interrelations of items (keywords), conceptual fields and topics as well as semantic inter-dependencies and networks - which are achieved through the development of a rule-based network of data (remarks) - are needed to generate both deeper knowledge and understanding about the semantic structures of this (re-) constructed Wittgenstein text. This knowledge expresses itself in the unique character of its organisation and structure and could help to build the basis for further in-depth investigations and analysis concerning specific topics related to Vermischte Bemerkungen. In coherence with the core objectives of the analysis of the German text version (Vermischte Bemerkungen) an encoding of the 1st and 2nd English edition (Culture & Value) will be done for the purpose of comparison and exploration in terms of textual semantic similarity and deviation.

So finally, these findings will provide the basis for further investigations concerning such questions as the following:

- What kind of text is this?

- Is the secret code in Wittgenstein’s remarks of any significant importance?

- Is there a Wittgensteinian philosophy of culture according to the patterns and networks identified?

Literature

- Miller, George A. 1956 “The Magical Number Seven, Plus or Minus Two: Some Limits on our Capacity for Processing Information” in Psychological Review, 63. London: Harvard University Press, 81-97.

- Wittgenstein, Ludwig 1998 Culture and Value, A Selection from the Posthumous Remains, edited by Georg Henrik von Wright in Collaboration with Heikki Nyman, revised edition of the text by Alois Pichler, translated by Peter Winch. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Zelger, Josef 1996 Linguistic Knowledge Processing by GABEK. The Selection of Relevant Information from Unordered Verbal Data. Paper at the International Conference on Conceptual Knowledge Processing. TH Darmstadt, Faculty of Mathematics, February. Preprint Nr. 42. Universität Innsbruck: Institut für Philosophie.

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.