Abstract

The Oxford Dictionary defines Text as “the original words of author” and Context as “parts that precede or follow a passage and fix its meaning; ambient conditions.” If we explicate text as any cognitive sign operation and context as the conditions on which we interpret the meaning of the text, then a text without context has no meaning. Common knowledge is that we fix meanings by interpretation, but how may we explicate the interpretation of text in context? I will discuss some major problems of text and context in theories of interpretation and how to overcome the predicaments of “hermeneutic universalism” and “hermeneutic contextualism” which involve either indefinite series of interpretations or interpretive vicious circle since there are no external grounds that would warrant the validity of interpretation. According to pragmaticist epistemology, every cognitive operation involves interpretation, and the question is if we can interpret the meaning of the text without being entangled in the paradoxes of phenomenological hermeneutics. I suggest that the criterion of the true interpretation of meanings is the proof-conditions of the text which are its specific truth-conditions, the mental and social conditions of the speaker, scientist, or the artist creating the artwork, and the proof method, namely the procedure to prove or quasi-prove the true interpretation of the text upon its truth-conditions.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction: Can We Have Text without Context?

- 2. Can the Language-game be the Context of the Textual Meaning?

- 3. Different Contexts of the Same Text Can Allow Different True Interpretations of Its Meaning.

- 4. Hirsch on Validity in Interpretation without Truth.

- 5. The Context as the Proof-Conditions to Prove the Truth of Our Interpretation of the Text.

- 6. Conclusion: If the Context of Text Is Its Proof-Conditions What Are Their Proof-Conditions?

1. Introduction: Can We Have Text without Context?

The Oxford Dictionary defines Text as "the original words of author" and Context as "parts that precede or follow a passage and fix its meaning; ambient conditions." If we explicate text as any cognitive sign operation, as verbal and non-verbal cognitive behavior and creations, and context as the conditions upon which we interpret the meaning of the text, then a text without context has no meaning (Eco, 1979). So what is the context and its function in conducing fixed meaning to text? The question is how to understand the concept of context; how upon the "ambient conditions" we fix the meaning of the text, which cannot be done without the context (Searle, 1979). In discussions of context the usual explanations are very general and vague so we have to fix the meaning of context (Stout, 1982). The common knowledge is that we fix meanings by interpretation, but how may we explicate the interpretation of text in context? I will discuss some major problems of text and context in theories of interpretation and how to overcome the predicaments of "hermeneutic universalism" and "hermeneutic contextualism." If universalism means that everything is interpretation we are apparently involved in an indefinite series of interpretations, and contextualism implies that truth is relative to some interpretive vicious circle since there are no external or outside grounds that would warrant the validity of interpretation (Hiley, 1991; Bernstein, 1983; Palmer, 1969).

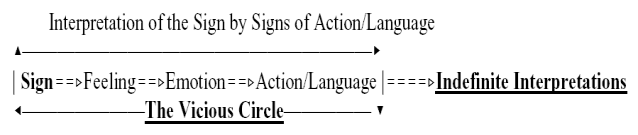

[1] The Two Phenomenological Predicaments in Interpretation of Cognitive Signs:

Assuming that every cognitive operation involves interpretation, the question is if we can interpret, understand, and explain the meaning of the text without being entangled in the paradoxes of phenomenological hermeneutics (Heidegger, 1930; Craige, 1983; Guignon, 2002; Nesher, 2002-2005).

2. Can the Language-game be the Context of the Textual Meaning?

Wittgenstein understood the difficulties of an endless series of interpretation and attempted to find a solution to this predicament by rejecting the function of interpretation in understanding the meaning of text and looking into criteria for teaching and learning the meaning of words through their use in the language-games (Wittgenstein, 1953). In analyzing Wittgenstein's conception of explanation of meaning of a word in its use in the language it can be shown that knowledge of the meaning of words must precede their use in language, otherwise we cannot know how to use them (Nesher, 1992). What can be the criterion for teaching and learning the meaning of the word in the language-game? We face a Fregean difficulty because if the criterion is a private-subjective experience how do we know that persons experience the same phenomenon? And if the criterion is external to the language-game and to our experience, how do we know that our experience represents it truly (Wittgenstein, 1969; Guignon, 2002)? Thus we have to revise Wittgenstein's Grammatico-Phenomenological conception of criteria with the pragmaticist theory of meaning and truth. The criterion of meanings should be the proof or quasi-proof, as with perceptual judgments, of the truth of their interpretation in propositions that make them clear by being true representations of reality. However, without confrontation with and representation of reality independently of the text and its context we cannot explain the operation of interpretation, its truth, and how we fix the meaning of the text. Yet if we can know the meaning of a text only through the context, then the context must be the conditions of our instinctive and practical quasi-proofs or rational proofs of the truth of our interpretation of the text. In my pragmaticist theory the criterion of the true interpretation of meanings must be the proof-conditions of the text which are its specific truth-conditions, the mental and social conditions of the speaker, scientist, or the artist creating the artwork, and theproof method, (withepistemic logic not just formal deduction), namely the procedure to prove or quasi-prove the true interpretation of the text upon its truth-conditions (Nesher, 2005).

3. Different Contexts of the Same Text Can Allow Different True Interpretations of Its Meaning.

This understanding of interpreting text also solves an essential difficulty in the theories of interpretation: are interpretations a matter of opinions and always relative to the interpreters, so that different interpretations of the same text are incompatible (Garcia, 1999)? Ricoeur suggests understanding text as an entity, a kind of semantic autonomy, as if language and even actions have meanings independent of their agents, as in the Fregean-Russellian formal semantic conception of the sentence (Ricoeur, 1976; Wimsatt and Beardsley, 1954; Barthes, 1971; Hirsch, 1967). Ricoeur accepts the formal semanticist position when the autonomous text refers by itself to the world through "the genuine referential power of the text" (Ricoeur, 1976), since otherwise there is only the interpreter's subjective meaning or the author's subjective intentional meaning in creating the text, which we cannot reach (Fish, 1980). Without any criterion for interpretation of the text how do we know that we understand the genuine referential power of the text "disclosing a world that constitutes the reference of the text?" We must know this "world" in order to interpret the text because otherwise we enter either into indefinite interpretations or into a vicious circle of hermeneutics. However, we can know the world represented by the text through our knowledge of the world of the creator of the text. We learn the initial meaning of texts by being ostensively taught the language in our culture through true interpretation of our perceptual experience representing our world. And when we encounter a text that belongs to our culture we interpret it instinctively in the common way, what Ricoeur calls a "guess" (Ricoeur, 1976; Hirsch, 1967). Sometimes, when we are not certain about our initial interpretation of the text, we continue on, explaining it by a rational interpretation called exegesis (Fish, 1980; Stecker, 2003). Our knowledge of the proof-conditions, which include the author's intentional spirit and the images and emotions embedded in her language, is always relative and develops with the inquiries the interpreters make about them (Jakobson, 1987; Wimsatt and Beardsley, 1954; Hirsch, 1967; Barthes, 1968; Carroll, 1997). Therefore, based on different methods of inquiry operating upon different truth-conditions, the interpreters can prove true different interpretations of the same initial meaning of text. Thus the sametext can have different true interpretations if they are based upon different contexts, so that they intersect but do not contradict (Hirsch, 1967; Margolis, 2002). Therefore, there is no "conflict of interpretations" between different true interpretations since they are based on different proof-conditions of the same text (Hirsch, 1967; Ricoeur, 1969; Stout, 1982; Barnes, 1988; Thom, 2000). However, since there can also be false and doubtful interpretations, only different true interpretation are compatible (Krausz, 2002).

4. Hirsch on Validity in Interpretation without Truth.

The question is how can context stabilize the meaning of the text as its significance. According to Hirsch the main criterion for the validity of the interpretation of the text is the coherence of its components' meanings (Hirsch, 1967, 1976). The problem is how to find the coherence of the initial meaning of the text since the interpreter's coherence of its meaning may deviate from the author's intended coherent meaning of the text. The principles or laws of "the criterion of coherence" operating our interpretation of the text cannot be formal artificial ones since they have to explain human cognitive behavior of interpretation whose truth depends on the true representation of reality. To understand the original meaning of the text we have to understand the author's meaning and the truth of his text in representing reality (Nesher, 2004). Hirsch's basic difficulty is with accepting the Husserlian phenomenological epistemology which cannot explain human confrontation with reality, hence also the proof of the truth of our interpretation of the initial meaning, the "verification" of its significance (Hirsch, 1984). So interpretation is thoroughly circular: "the context is derived from the submeanings and the submeanings are specified and rendered coherent in reference to the context" (Hirsch, 1967). Validation of the interpretation of the meanings as the Husserlian experiential-intentional objects should place an independent restriction on finding common ground between the meaning of the author's text and its interpreter's. Moreover, Hirsch holds the Popperian conception of absolute truth, namely that since we cannot prove it but only refute our hypothetical theories we will never know whether the truth has been reached. Thus he rejects the possibility of verifying the truth of our interpretations of texts, and thereby of stabilizing their meanings. The question is how we prove the truth of interpretation of the text, which is always limited and relative to its known proof-conditions.

5. The Context as the Proof-Conditions to Prove the Truth of Our Interpretation of the Text.

The proof of the true interpretation of the text upon its proof-conditions is by its true representation of reality. This can be explained only through confrontation with reality, both physical and psychical, such that interpretation of cognition and representation of reality are the twin components of the cognitive operation of mind.

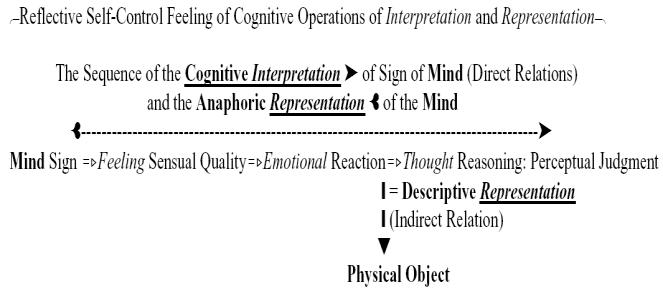

[2] Siamese Twins of Interpretation of Meaning and Representation of Reality:

We cannot represent physical reality without representing our own cognitive minds, and vice versa. So we represent physical reality when we prove it cognitively and we represent psychological reality when we prove its interpretation on the constraints of physical reality. Thus the interpretation of mind's cognitive signs is the essential twin component of the representation of both physical and psychical reality (Iser, 2000; Thom, 2000). With this understanding of our cognitive minds we can avoid both the indefinite series of interpretations of "hermeneutic universalism" and the vicious circle of "hermeneutic contextualism" (Habermas, 1998). Through confrontation with reality with our reflective self-control of interpretation of the initial vague meaning we can continue to quasi-prove or prove, locally, the truth of our cognitive interpretation and representation of reality on specific proof-conditions. One can call the instinctively and practical interpreted meaning the meaning, and the rationally proven true interpretation of the initial meaning, its exegesis, significance (Gadamer, 1960; Hirsch, 1967, 1984). Yet interpretation can go beyond the initial meaning of the text, into its Reconstruction according to our knowledge of the author's intended spirit of the text. Still, we have to distinguish between the interpretation of the initial meaning of the original text as Significance and its Application to new historical proof-conditions which might be foreign to the author of the text (Gadamer, 1984; Hirsch, 1984). To explain the conception of context as the proof-conditions we can start with our perceptual judgments as our basic factual knowledge and ask what is context for their meanings (Peirce, CP). The proof-conditions of perceptual judgment are the method of quasi-proving the perceptual judgment upon itstruth-conditions (Nesher, 2002:V, X).

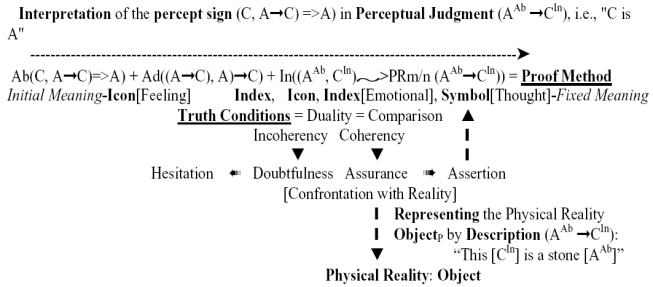

[3] The Context of Perceptual Judgment Text Is Its Proof-conditions

The general cognitive method is the Peircean trio, the sequence of the inferential rules of Abductive Discovery (Ab), Deductive Expectation or Prediction (Dd), and Inductive Evaluation (In), to prove the truth of the interpretation of the meanings of our texts. Thetruth-conditions of our perceptual judgments are the relations between its cognitive components, the Iconic Feeling of an object and the Indexical Emotional reaction to it. By continuously reflecting on them instinctively and practically we feel their coherence as the condition for their synthesis in truly interpreting the meaning of the perceptual judgment (Nesher, 2002). However, the applications of this general cognitive method of proof are specific to any field of inquiry and its particular truth-conditions (Hirsch, 1967).

6. Conclusion: If the Context of Text Is Its Proof-Conditions What Are Their Proof-Conditions?

As I have theorized elsewhere, facts are our proven true propositions and genuine facts are our quasi-proven true perceptual judgments as our basic contexts upon which we prove the truth of interpretations of other propositions and theories (Nesher, 2002:X). Therefore, contexts are not given arbitrarily and not self-proven or self-defined but are proven true in our cognitive confrontation with reality. The proof of the truth of any proposition or hypothesis is always relative to its proof-conditions (Hirsch, 1967; Wachterhauser, 2002). The relative advantage of one true interpretation over another is in respect to how their different proof-conditions comprehend the subject matter of the interpretation and representation (Thom, 2000). There is no absolute proved truth but only local truths, although as in our scientific, aesthetic, and other cognitive activities representing reality, they evolve and extend as we develop the proof-conditions to represent reality better (Croce, 1901; Nesher, 2002: X). So it is similarly with our interpretive activities, when we develop our proof-conditions of the text to understand its meaning better by proving the true interpretation; thus true interpretations with different proof-conditions can continue indefinitely (Stout, 1982; Margolis, 1995; Nesher, 2002; Krausz, 2002, Habermas, 2003). We can follow the Peircean epistemology showing that the trio of Abduction, Deduction, and Induction is our basic epistemic complete method to prove the truth of our interpretations of texts as representation of reality. Hence the truth of this method itself cannot be proven by one of these logical inferences, and so nor can any one of them prove another, and thus surprisingly only when the trio comprises the entire sequence of these inferences can we prove its truth. I claim that by self-controlling our local proofs as true interpretations and representations of reality, in a long run we prove this trio as conducing truth relative to our truth-conditions, hence as a relative true method of proof.

Literature

- Barnes, A. (1988)On Interpretation: A Critical Analysis. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Barthes, R. (1968) "The Death of the Author." In Ronald Barthes, The Rustle of Language. Translated by R. Howard. Berkeley: University of California press 1989:49-55.

- Barthes, R. (1971) “From Work to Text.” In Ronald Barthes, The Rustle of Language. Translated by R. Howard. Berkeley: University of California press 1989:56-64.

- Bernstein, R. (1983) Beyond Objectivism and Relativism: Science, Hermeneutics, and Praxis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Carroll, N. (1997) "The Intentional Fallacy: Defending Myself." The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 55, No. 3, 1997:305-309.

- Craige, B.J. (1983) "What Is Relativism in the Arts." In Craige, B.J., ed.,Relativism in the Arts. Athens, GA: University of Georgia Press, 1983:1-20.

- Croce, B. (1901) The Aesthetic as the Science of Expression and the Linguistic in General. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1992.

- Eco, U. (1979) The Role of the Reader. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Fish, S. (1980) Is There a Text in the Class? The Authority of Interpretive Communities. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Gadamer, H-G. (1960) Truth and Method. New York: Crossroad 1989.

- Gadamer, H-G. (1964) “Aesthetic and Hermeneutics.” In his Philosophical Hermeneutics.

- Gadamer, H-G. (1984) “Text and Interpretation.” In Wachterhauser, B.R. ed., (1986) Hermeneutics and Modern Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press: 377-415.

- Garcia, J. J. E. (1999) “Relativism and the Interpretation of Texts.” In Margolis, J. & T. Rockmore, eds., The Philosophy of Interpretation. Oxford: Blackwell 2000:43-62.

- Guignon, Ch. (2002) "Truth in Interpretation: A Hermeneutic Approach." In Krausz, M., ed., 2002:264- 284.

- Habermas, J. (1998) On the Pragmatics of Communication. Edited by M. Cooke. Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

- Habermas, J. (2003) Truth and Justification Cambridge Mass.: MIT Press.

- Heidegger, M. (1930) “On the Essence of Truth.” In Martin Heidegger: Basic Writings. Edited by D.F. Krell, New York: Harper-Collins, 1977:111-138.

- Hiley, D.R. et al., eds. (1991) The Interpretive Turn: Philosophy, Science and Culture. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Hirsch, E.D. Jr. (1967) Validity in Interpretation. New Haven: Yale University Press: Context, 86ff.

- Hirsch, E.D. Jr. (1976) The Aims of Interpretation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

- Hirsch, E.D. Jr. (1984) “Meaning and Significance Reinterpreted.”Critical Inquiry, Vol. 11, No. 2 Dec. 1984:202-225.

- Iser, W. (2000) The Range of Interpretation. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Jakobson, R. (1987) Language in Literature. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Krausz, M., ed. (2002) Is There a Single Right Interpretation? University Park, Penn.: Pennsylvania State University Press.

- Margolis, J. (1995) Interpretation Radical but not Unruly: The New Puzzle of Arts and History. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Margolis, J (2002) "'One and Only One Correct Interpretation'." In Krausz, M., ed., 2002:26-44.

- Nesher, D. (1992) "Wittgenstein on Language, Meaning, and Use." International Philosophical Quarterly Vol. XXXII, No. 1, March 1992.

- Nesher, D. (2002) On Truth and the Representation of Reality. Lanham: University Press of America.

- Nesher, D. (2003) “The Beauty of Artworks Is in Their Aesthetic True Representation of Reality: The Epistemology of Creation, Interpretation And Evaluation of Artworks as an Aesthetic Language Representing Reality.” Presented at the International Society of Phenomenology, Fine Arts, and Aesthetic: The Eighth Annual Conference. Harvard Divinity School, May 16-18 2003.

- Nesher, D. (2004) “Meaning as True Interpretation of Cognitive Signs: A Pragmaticist Alternative to the Shortcomings of Analytical Philosophy and Hermeneutic Phenomenology Conceptions of Meaning, Interpretation, and Truth.” Presented at the Conference on Meaning and Its Meanings. December, 2004, University of Haifa.

- Nesher, D. (2005) “Can Wittgenstein Explain Our Knowledge of Meaning? Pragmaticist Revision of His Conceptions of Interpretation and Criteria.” Presented at the 28th Wittgenstein International Symposium, Kirchberg, Austria, August, 2005. Published in the volume of the symposium: Time and History. Vienna: Holder-Pichler-Tempsky. Kirchberg 2005.

- Palmer, R.E. (1969) Hermeneutics: Interpretation Theory in Schleiermacher, Dilthey, Heidegger, and Gadamer. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1969.

- Peirce, C.S. (1931-1958) Collected Papers, Vols. I-VIII, Harvard University Press. [CP]

- Ricoeur, P. (1969) The Conflict of Interpretations. Evanston: Northwestern University Press 1974.

- Ricoeur, P. (1976) Interpretation Theory: Discourse and the Surplus of Meaning. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press.

- Searle, J. (1979) Expression and Meaning: Studies in the Theory of Speech Acts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: Chap. 5–Literal Meaning (on meaning and context).

- Stecker, R. (2003) Interpretation and Construction: Art, Speech and the Law. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Stout, J. (1982) "What is the Meaning of a Text?" New Literary History, Problem of Literary Theory, Vol.14, No.1, 1982:1-12.

- Thom, P. (2000) Making Sense: A Theory of Interpretation. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield Publishers Inc.

- Wachterhauser, B.R. (2002) “Getting it Right: Relativism, Realism and Truth.” In Dostal, R.J., ed., Cambridge Companion to Gadamer. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 2002:52-78.

- Wimsatt, W.K. and M.C. Beardsley (1954) "The Intentional Fallacy." The Verbal Icon. University of Kentucky Press, 1954:3-18.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations, Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1969 (PI).

- Wittgenstein, L. (1969) On Certainty, Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.