Abstract

Dealing with how our cognitions represent reality we have to inquire how they can represent it truly. We start from our perceptions in order to continue to other modes of representing reality: scientific, ethical, and aesthetic. These three modes of representations echo Kant’s three Critiques, although he did not see them all as modes of representing reality. Therefore we have to turn the tables on his Copernican Revolution to overcome the basic transcendental epistemology. I analyze briefly Wittgenstein’s two philosophical systems as prototypes of the Analytic Philosophy of formal semantics and the Phenomenology of interpretation, show their difficulties, and suggest Peircean Pragmaticism as an alternative to deal with how the languages of artworks represent reality aesthetically. Aesthetic representation by allegories differs from Scientific representation by general theories and from the Ethical representation by moral norms guiding our lives. However, only through our confrontation with reality these three cognitive enterprises can represent reality, which cannot be explained by the Analytic Metaphysical Realism or Phenomenological Internal Realism, being severed from reality.

Table of contents

- 1. Introduction: Language, Reality and the Problem of Representation

- 2. Language and Reality in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus

- 3. Language and Representation in Wittgenstein’s Late Philosophy

- 4. Wittgenstein on Aesthetic Judgments of Artworks

- 5. The Meaning and Truth of Languages of Artwork Represent Reality

- 6.Epistemology of Artwork, Its Truth and Beauty Representing Reality

1. Introduction: Language, Reality and the Problem of Representation

Dealing with how our cognitions represent reality we have to inquire whether and how they can represent it truly. We start from our perceptions in order to continue to other modes of representing reality: scientific, ethical, and aesthetic. These three modes of representations echo Kant’s three Critiques, although he did not see them all as modes of representing reality. Therefore we have to turn the tables on his Copernican Revolution to overcome the basic transcendental. I analyze briefly Wittgenstein’s two philosophical systems as prototypes of the Analytic Philosophy of formal semantics and the Phenomenology of interpretation, show their difficulties and suggest Peircean Pragmaticism as an alternative to deal with how the languages of artworks represent reality aesthetically. Aesthetic representation by allegories differs from Scientific representation by general theories and from the Ethical representation by moral norms guiding our lives. However, only through our confrontation with reality these three cognitive enterprises can represent reality, which cannot be explained by the Analytic Metaphysical Realism or Phenomenological Internal Realism, being severed from reality.

2. Language and Reality in Wittgenstein’s Tractatus

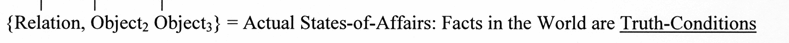

2.1. Wittgenstein Distinguishes between Reality and World to Explain the Meaning and the Truth

I take Wittgenstein’s Tractatus as the prototype of the enterprise of the formal semanticists to explain through model theory our representation of external reality. The Tractarian system is embedded in a Kantian metaphysics, with the assumption of Metaphysical Objects and Metaphysical Subject which are necessary to explain how language represents reality. In the Tractatus Wittgenstein constructed his logico-philosophical semantics that attempts to explain through the concepts of meaning and truth how thoughts expressed in language represent eternal objects of external Reality and describe facts in the World. Wittgenstein’s pictorial theory of representation is a device to show the correspondence of our propositions through the correspondence between the elements of the propositional signs and the objects that compose the facts that verify it. How does such correspondence hold between the senses expressed in language and states of affairs in reality and facts in the world? According to Descartes, Hume, and Kant, we cannot go outside our cognitions to compare language with external reality. According to Wittgenstein, “It is impossible to tell from the picture alone whether it is true or false” (T:2.224).

2.2. The Metaphysical Subject Representing Reality Pictorially and Describing Worldly Facts

How can facts in the World be known to determine whether the elementary propositions represent them truly? In the Tractatus the Metaphysical Subject is the only one that can use the Tractarian elementary propositions to represent reality and describe facts since there are no empirical subjects in the Tractarian World. The Metaphysical Subject is like the Cartesian God staying outside the World, not like humans who are prisoners in their minds. The Metaphysical Subject has separate access to propositional facts and to bare facts, which enable it to compare their logical forms and thus to determine the truth of the elementary propositions and this it can do only from outside the World.

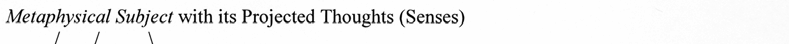

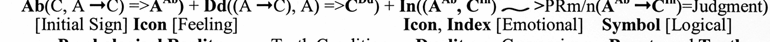

- [1] Wittgenstein’s Conceptions of Meaning and Truth

[See Diagram 1]

In the Tractatus we should distinguish between the role of Wittgenstein, as the formal semanticist, constructing this system with his philosophical language to show how language represents reality, and the role of the Metaphysical Subject, with the only language which it understands, the descriptive language of natural science (T:5.61). In this system the Metaphysical Subject relates its language to the Metaphysical objects, when both are outside the empirical World, like Kant’s noumena.

2.3. Why Cannot the Pictorial Theory of Representation Explain Human Representation of Reality?

However, abstract idealizations of formal semantics cannot preserve the essential relations of mind representing reality. The interpretation of the linguistic expressions in entities of the abstract structure assigned to them by the formal semanticists from outside these idealized domains assumes a God’s-eye-view which humans cannot attain, and it can only create an illusion of a theoretical solution by assuming dogmatically the existence of external objects and facts to which linguistic expressions relate. But language is human cognition, and we are the pictures that we cannot compare from outside with external reality. Can we make this comparison without “get outside our skins” (Davidson, 1986; Nesher, 2002)?

3. Language and Representation in Wittgenstein’s Late Philosophy

3.1. THE Grammatical Language-Game and the Operation of Rules of Meaning and Truth

Wittgenstein's philosophical investigations are severed from empirical science, and this raises difficult questions about the relationship of the “grammatical phenomenology” of a language‑game to empirical reality, hence to the entire explanation of meaning and truth. To understand this cleavage between these two domains, we must examine the distinction between the functions of the internal relations of meaning and those of the external relations of empirical propositions. The internal relations are constitutive and compose the grammatical rules of meaning forming the relation between linguistic expressions and their meaning criteria with necessity connective ! of internal relations.

- [2] Grammatical Rules of Meaning:

- Meaning(Word) = Ri(Word !Criterione/i)

where M(W) is the meaning of W, Ri is the grammatical operator of the internal relation of meaning, W is the linguistic expression, and C is the criterion of the meaning of W (an extra-linguistic Ce or "in the language"). External relations are between empirical propositions or theories and the symptoms, empirical evidence, allegedly determining their truth values. Propositional beliefs and theoretical hypotheses are connected Inductively to their symptoms with the probability connective ∈>, by external relations.

- [3] Empirical Inductive Rule of Truth:

- Truth(P) = Re((Proposition, Fact) ∈>PRm/n(P !F))

where P is the empirical proposition, Re is the operator of the empirical inductive rule of inference of truth, F is the symptom-fact for the truth of P, and ∈>PRm/n(P !F) is the inductive inference of probability from the proposition P and the symptom-fact F to the “warranted assertability” that P !F confirms the truth of P. The entire operation in a language-game is the combination of the internal rule of meaning [2] with the external rule of truth [3].

- [4] The Grammatical Language-Game Operation of Meaning and Truth

- Meaning(W) = Ri(W !Ce/i) + Truth(P(W)) = Re((P, F) ∈>PRm/n(P !F))

Accordingly, the rules of meanings are essential constituents of the grammatical structure of empirical propositions. The truth evaluation of linguistic propositions (Ps) presupposes their meanings, hence it cannot affect the meanings but only the truth of these expressions.

3.2. Why Language-Games Cannot Represent External Reality

Are empirical evidence-symptoms elements of language-game or of reality outside it?

The thing that's so difficult to understand can be expressed like this. As long as we remain in the province of the true-false games a change in the grammar can only lead us from one such game to another and never from something true to something false. On the other hand if we go outside the province of these games, we don't any longer call it 'language' and 'grammar', and once again we don't come into contradiction with reality. (Wittgenstein, PG#68; cf. OC#191)

“The province of the true-false games” is the language‑games with their criteria and evidential symptoms being our form of life, which we cannot go outside of.

But I did not get my picture of the world by satisfying myself of its correctness; nor do I have it because I am satisfied of its correctness. No: it is the inherited background against which I distinguish between true and false. (Wittgenstein, OC#94)

How do we know that the evidence or symptoms of the inherited background are true empirical propositions upon which we can prove the truth or falsity of judgments? They are given without being proved true since for this we have to confront them with external reality. Since in the autonomous language-game this confrontation is impossible we accept the inherited background as a myth, as our conventions. “The propositions describing this world picture might be part of a kind of mythology” (OC#95). This is also the status of Popper’s “empirical basis” which without being proved true is only doubtful and cannot be the basis of falsification (Nesher, 2002:X).

3.3. The Problem of Mental Meaning and the Quasi-proof of Our Basic Perceptual Propositions

Wittgenstein, in efforts to overcome the subjective explanation of meaning that brought him to Solipsism in his early period, argues against the possibility of “private” language of feelings, images, and emotions. Accordingly, inner mental states are not meaning elements of the language-game and do not affect our linguistic behavior. Hence Wittgenstein’s grammatical phenomenology cannot explain our confrontation with reality since only through our mental reflective self-control of the perceptual operations we can quasi-prove the truth of our perceptual judgments representing external reality (PI#293; Nesher, 1987).

4. Wittgenstein on Aesthetic Judgments of Artworks

Wittgenstein describes and compares the use of words expressing aesthetic judgments in order to understand the grammatical rules of a language-game of aesthetic words, their meaning and use.

The words we call expressions of aesthetic judgments play a very complicated role, but a very definite role, in what we call a culture of the period. To describe their use or to describe what you mean by cultured taste, you have to describe a culture. (To describe a set of aesthetic rules fully means really to describe the culture of the period). … An entirely different game is played in different ages. (Wittgenstein,L&C:I#25)

What belongs to a language game is a whole culture… (Wittgenstein,L&C:I#26)

The context of the creation and the evaluation of artworks is essential to understanding their meaning, and thus the concept of culture in explaining aesthetic judgments is essential, but only if we can explain its epistemic function as the proof-conditions to prove the truth, hence the aesthetic beauty, of their interpretations and representations of reality (Nesher, 2007b).

I see roughly this–there is a realm of utterance of delight, when you taste pleasant food or smell a pleasant smell, etc., then there is the realm of Art which is quite different, though often you may make the same face when you hear a piece of music as when you taste good food. (L&C:II#3)

Wittgenstein feels the distinction between sensual taste and Art, but since he deals basically with our instinctive and practical reactions he does not elaborate any epistemological explanation of the cognitive function of Art in its aesthetic representation of our reality. Also, in the aesthetic language-game it is impossible for us to understand this representation while prisoners of its framework, as shown above.

5. The Meaning and Truth of Languages of Artwork Represent Reality

5.1. The epistemology of confrontation with reality to prove the truth or falsity of cognitions

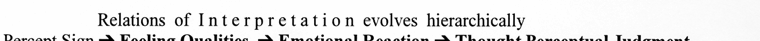

The problem is to explain whether and how we confront reality to self-control the meaning and truth of artworks to determine their aesthetic beauty. The aesthetic meaning-content of artwork originates in the artist’s experience, such that from the meaning-content of perceptual experience the intellectual understanding of reality is developed in interpretation by abstraction and generalization (Nesher, 2002:II). The subjective feelings of qualities and emotional reactions to them are essential components of any experiential meaning-content. They can become objective when the entire cognitive operation is synthesized in perceptual judgment, in reasoning thought, or in aesthetic judgment of taste, and through confrontation with reality proved to be true interpretation and representation (Nesher, 2005). The meaning-content of our basic propositions evolves hierarchically in perception from pre-verbal sensory-motor Feeling andEmotion as the meaning-content of the Perceptual Judgment ofThought:

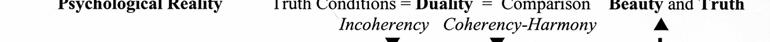

- [4] Perceptual Experience of Interpretations and Representation and its Meaning-Content

- [See Diagram 2]

The signs that eventually represent the Real Object are the Iconic sign, the Feeling of the Property P of the Object, the Indexical sign, the Emotional Reaction to Feeling: [this] K. When coherent they are synthesized in theSymbolic sign Thought, a perceptual judgment: “[This] K is the Object presented in P.”

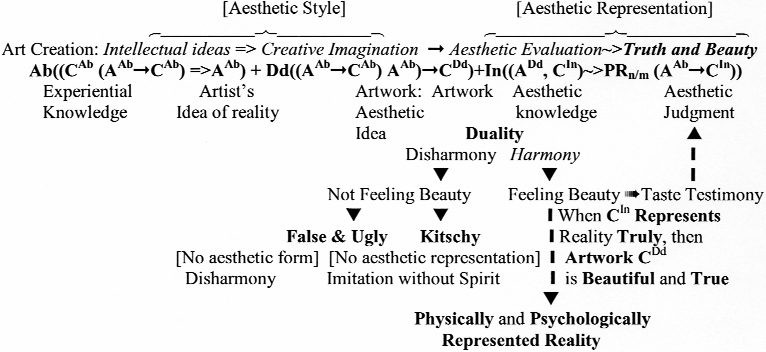

5.2. Artistic Creation from Intellectual Understanding of Reality to Its Aesthetic Exhibition

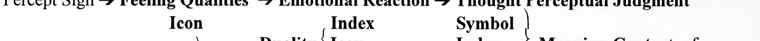

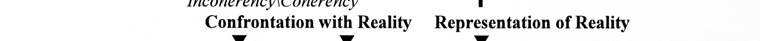

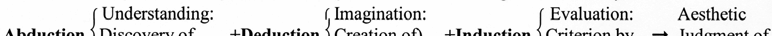

Aesthetic knowledge and its function in human life have the same epistemology as Science and Ethics to explain human cognitive representation of reality. Indeed, neither scientific theories nor literary artworks are fictional, but they are all human cognitions representing reality albeit in different cognitive modes. The “atom” and “electron” of science are not proper names but general names of similar objects; and the literary “Don Quixote” and “Anna Karenina” are not proper names of real persons but general names of characters and motivations of humans in general (Goodman, 1984). Artistic creations are based on human experience evolving into general intellectual ideas representing reality which are interpreted by being epitomized in aesthetic ideas as modes of representation. The aesthetic modes of representations exhibit particular characters and situations representing types in reality. Following is the Pragmaticist scheme of artistic creation, the Trio of Abductive discovery, Deductive elaboration, and Inductive evaluation:

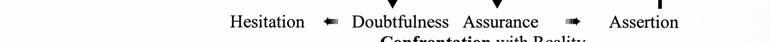

- [5] The Sequence of Interpretation: Discovery of Intellectual Idea Creation of Aesthetic Idea Synthesized by their Harmony as Criterion of Judgment of Beauty:

[See Diagram 3]

This is an elaboration of Kantian aesthetics, but the question is about the conception of Harmony if it can be an objective criterion of beauty (Kant, CJ). This brings Kant’s aesthetic theory to the paradox of beauty, as in Wittgenstein’s paradox of the meaning of following rules, which if every subjective pleasure determines beauty, and every displeasure can contradict it, such subjective feelings cannot be an intersubjective Judgment of beauty. Hence, there is no phenomenal objective criterion for harmony between intellectual ideas and aesthetic ideas, and the judgment of aesthetic beauty remains arbitrary. The way out from such “internal realism” is the epistemology of pragmaticist “representational realism.”

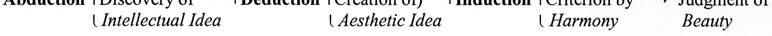

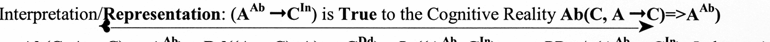

5.3. Proof of Truth and Beauty of Artworks: The Nature of Aesthetic Representation of Reality.

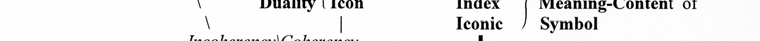

Epistemic logic is the sequence of trio inferences, and is the same general method of proving the cognitive representation of reality and of the creation and evaluation of artwork. The epistemology of confrontation with Reality is the complete quasi-proof of perceptual judgments and proofs of more abstract propositions.

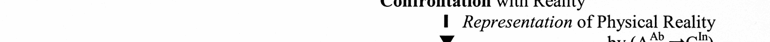

- [6] The Structure of Complete Proof of True Interpretation and Representation of Reality:

[See Diagram 4]

Thus, => is a plausibility connective suggesting the concept, or theory, AAb from the perceptual experience CAb and the quasi-deductive rule (A!C), the ! is a necessity connective deducing the abstract object CDd from the rule (A!C) and the Abductively suggested AAb; since the abstract object CDd is contained in AAb, we evaluate the latter against the newly experienced CIn in Induction when ∉> is a probability connective evaluating the relation of the concept/theory AAb and the new experiential object CIn to prove the proposition (AAb!CIn). With complete proof we confront reality by the Abductively discovered suggestions, Deductively elaborating them, and their Inductive evaluation, without trying in vain to justify separately any a priori concepts, principles, and rules, as Kant strives to do in his Critiques (Kant, Logic:#II; Nesher, 2007).

6.Epistemology of Artwork, Its Truth and Beauty Representing Reality

6.1. Artistic Creation of Artwork as Beautiful Is Self-consciously Reflective Self-controlled

The aesthetic evaluations of artistic works as beautiful are self-conscious reflective judgments by the artists of their own creative-interpretative operations and by others through their interpretations of artworks. The artists' reflective judgments are based on instinctive and practical self-control and they also reach rational intuition, to self-control the free play between intellectual ideas of understanding reality and productive imagination in creating aesthetic ideas to achieve their harmony in the artwork (Kant, CJ). The Spinozist conception of freedom as determinate self-control can explain the artistic operation as critically appraising the creation and completion of artwork (Nesher, 1999). This harmony can be achieved only by some objective criterion common to both kinds of ideas, the proof of their truth in representing reality.

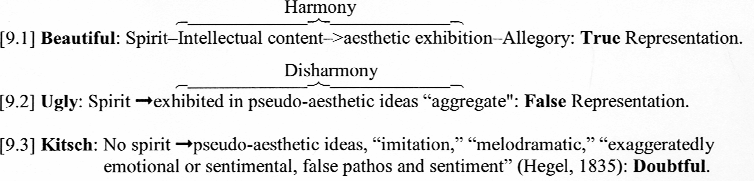

6.2. Evaluation of Created Artwork as True Aesthetic Representation of Human Reality

We start our evaluation of the aesthetically imaginative exhibition of artworks instinctively and practically, and of their intellectual content only through the interpretation of the former. The proof of true interpretation depends on our knowledge of the artist’s truth-conditions, which must be relative to our knowledge of the artist's initial “spirit,” his “intellectual ideas” and the reality he endeavors to represent aesthetically. This also shows why there can be differences in interpretations of the artwork's intellectual content and its aesthetic exhibition by different people. However, without understanding the artist's language and knowing his truth-conditions we cannot understand the artwork and judge its beauty as a true representation of reality. Artists reveal their Concepts of reality in their aesthetic exhibition of artworks representing reality. The truth of artwork is not superficial imitation of reality but the aesthetic exhibition of the artist's true Conceptions of it. Since artistic imitation cannot harmonize with true Conception of reality it cannot be its true representation. Artistic imitation of reality without spirit is a kitsch and the disharmony between the artist’s Conception and the aesthetic exhibition is false artwork.

6.3. The Artwork's Creation and Evaluation, and the Proof of Judgment of Its Truth and Beauty

Pragmaticist epistemology explains how the instinctive Reflective Act of Comparison between the Iconic aesthetic feeling ADd and indexical emotional reaction to it CIn, and the harmony between them, amounts to the feeling of aesthetic pleasure as the beauty of the aesthetic artwork. Since this can be achieved only when the artwork aesthetically represents reality, the feeling of aesthetic beauty is also the sense of the Truth indicating aesthetic knowledge of this reality.

For the whole question consists in that–what to consider as the truth. This is why the novel is written. (Dostoevsky, in Mochulsky, 1947)

The following are the threefold stages of the artistic creating and evaluation of Artwork:

- [7] The Artwork's Creation and Evaluation, and the Proof of Judgment of Its Truth and Beauty:

[See Diagram 5]

This is the artist's cognitive operation from his knowledge of reality to create the artwork with its continuous evaluations against such knowledge. If the artistic intellectual idea AAb is exhibited in the Artwork's aesthetic ideas CDd, then by evaluating Inductively the harmony in the meaning-content of the artwork, against the artist’s knowledge of reality, he can evaluate the artwork's truth and beauty. The Inductive inference ((AAb, CIn) ~>PRm/n (AAb–>CIn)) is the evaluation of the artwork CDd through the embedded intellectual artistic idea AAb as its meaning. We evaluate artworks by proving their being true and beautiful or false and ugly; artworks for which these cannot be proved are doubtful and kitschy.

- [9] Success or Failure of the Aesthetic Exhibition Affects the Beauty and Truth of Artwork:

[See Diagram 6]

When we know the reality that the artist represents aesthetically, the truth-conditions of his artwork, we can inquire into this distinction between true and false aesthetic representation of reality. Still, every rational analysis of artworks starts with our experiential feelings and emotional reaction to artwork as pleasure, or displeasure, as its beauty and truth. These emotional reactions to the true aesthetic representation of reality reflect our real lives, our understanding of ourselves, and lead to preparation to self-control our future life.

Literature

- Davidson, D. (1986) “A Coherence Theory of Truth and Knowledge.” In E. LaPore, ed., Truth and Interpretation. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Goodman, N. (1984) Of Mind and Other Matters. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Hegel, G.W.F. (1835) Hegel’s Aesthetics Lectures on Fine Art, Vol. I. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kant, I. (1790) Critique of Judgment. Trans. by W. S. Pluhar. Indianapolis: Hackett Publishing 1987 (CJ).

- Kant, I. (1800) Logic. Translation by R.S. Hartman and W. Schwarz. New York: Dover.

- Mochulsky, K. (1947) Dostoevsky: His Life and Work. Princeton: Princeton University Press 1967.

- Nesher, D. (1987) “Is it Really That ‘The Thing in The Box Has No Place in The Language‑game at All’ (PI#293)? A Pragmatist Alternative to Wittgenstein's and Putnam's Rejection of Mental Meaning.” Presented at the13th International Wittgenstein Symposium, Kirchberg, Austria, August 1987.

- Nesher, D. (1999) “Spinoza’s Epistemology of Freedom.” Presented at the conference on Spinoza by 2000: Ethics V: Love, Knowledge, and Beatitude - The Jerusalem Conference, June, 1999.

- Nesher, D. (2002) On Truth and the Representation of Reality. Lanham: University Press of America.

- Nesher, D. (2005) “Can Wittgenstein Explain Our Knowledge of Meaning? Pragmaticist Revision of His Conceptions of Interpretation and Criteria.” Presented at the 28th Wittgenstein International Symposium, Kirchberg, Austria, August, 2005.

- Nesher, D. (2007) “How to Square (Normo, CP:2.7) Peirceanly the Kantian Circularity in the Epistemology of Aesthetics as a Normative Science of Creating and Evaluating the Beauty of Artworks.” Presented at the Conference on Charles Sanders Peirce’s Normative Thought. June, 2007, University of Opole, Poland.

- Peirce, C.S. (1931-1958) Collected Papers, Vols. I-VIII, Harvard University Press (CP).

- Walton, K.L. (1990) Mimesis as Make-Believe. Cambridge Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Wittgenstein, L. (1921) Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul 1961(T).

- Wittgenstein, L. (1938) Lectures & Conversations on Aesthetics, Psychology and Religious Beliefs. Edited by Cyril Barrett. Berkeley: University of California Press (L&C).

- Wittgenstein, L. (1953) Philosophical Investigations. Oxford: Basil Blackwell, 1969 (PI).

- Wittgenstein, L. (1969) On Certainty. Oxford: Basil Blackwell (OC).

- Wittgenstein, L. (1974) Philosophical Grammar. Oxford: Basil Blackwell (PG).

Diagram 1

Diagram 2

Diagram 3

Diagram 4

Diagram 5

Diagram 6

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.