Abstract

Wittgenstein and Leibniz had a radically different view on the ultimate constituents of the world and resulting from this on the ontological status of the actual world in contrast to possible worlds. Whereas Leibniz thought that the world (the actual world) was chosen “as a whole” by God out of infinitely many alternative possible worlds, Wittgenstein believed that the world was a random conglomerate of mutually compatible “states of affairs”. For Leibniz no part of the actual world could be identical to a part of a different world. For Wittgenstein every part of the world had exact counterparts in other worlds. They both agreed on the importance of logic though, and they both shared a desire to explain the nature of contingency.

Table of contents

1. Leibniz’ Possible Worlds

It is well known that Leibniz introduced the concept of a possible world in an attempt to prove that the world as it is does not contradict the claim that God is all-mighty, all-knowing and all-good. The principle of an infinitude of possible worlds is part of his theodicy.

“I call ‘World’ the whole succession and the whole agglomeration of all existent things, lest it be said that several worlds could have existed in different times and different places.” (Theodicy, p. 128)

Notoriously, Leibniz held that this is the best of all possible worlds. This seemed to many a not very plausible view, but the interesting observation is that Leibniz thought that there were other worlds imaginable. He was contradicting Spinoza and Hobbes who believed that everything possible must exist.

Everything possible would indeed be existing (real) if it were the case that all possibles were “compossible”. Two individuals are said to be compossible if they are not only possible in isolation but also “capable of joint realization”. “A possible world is a set of mutually compossible complete individual concepts”. (Mates, p. 340). “The actual universe is the collection of all existent possibles [...] and as there are different combinations of possibles, some better than others, there are several possible universes, each collection of compossibles constituting one.” (Gerhardt, 1965, p. 573, quoted in Parkinson 1995, p. 213)

Thus, out of all possibles a subset of compossibles constitutes the world. According to Leibniz “all things which are possible, or express essence of possible reality, tend by equal right towards existence in proportion to the quantity of essence or reality which they include, or in proportion to the degree of perfection which belongs to them.” (Ultimate, p. 138) This could mean that the largest number of mutually compatible things exists. If there were 4 things A, B, C, D that were in essence similar and D were incompatible with A and B, but A were compatible with all but D, and B and C were also compatible then the series of ABC rather than CD would exist. (cf. Wahrheiten, p. 177) This is probably an overly simplified example, as Leibniz claims in other papers that the perfect world is determined instead of by the number of things by variety and simplicity. There is always, he says, “to be found in things a principle of determination which turns on considerations of greatest and least; namely, that the greatest effect should be produced with [...] the least expenditure.” (Ultimate, p. 138)

The question how a world must be constituted in order to be brought to existence, interesting as it is, is of secondary importance. In another line of reasoning Leibniz comes to the conclusion that the fact that this world exists is a proof that it must be the best of the possible worlds. This is a result of the principle of sufficient reason.

If God, so the argument goes, has to choose among the infinity of possible worlds, one to bring to existence he must of necessity choose the best one as only the best sticks out. For Leibniz (in contrast to Descartes) there can be no arbitrary choices, not any made by us and certainly not made by God. If we were told to draw a triangle, we would, says Leibniz, draw an equilateral triangle. If we have to go from a to b we take the shortest route, if there are no further qualifications. (Ultimate, p. 138).

This means that “if there were not the best (optimum) among all possible worlds, God would not have produced any”. (Theodicy, p. 128) And it also follows that God cannot just create anything but that He is restricted to possibles that “exist” independently of Him (although they are only ideas in His mind): “God’s decree consists solely in the resolution he forms, after having compared all possible worlds, to choose that one which is the best, and bring it into existence together with all that this world contains, by means of the all-powerful word Fiat.” (Theodicy, p. 151)

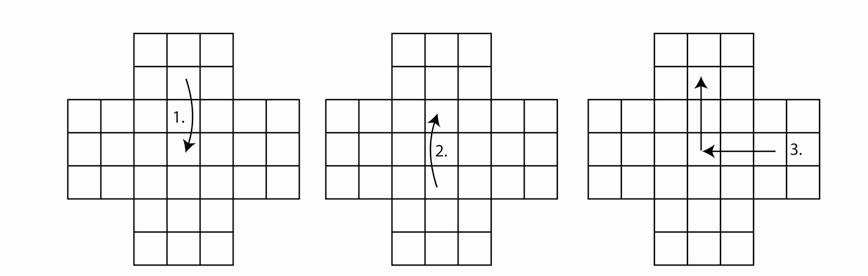

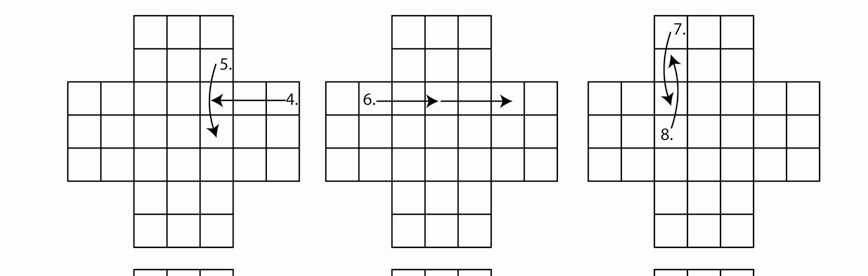

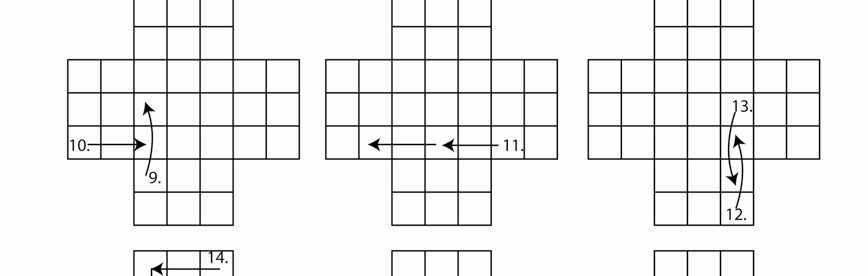

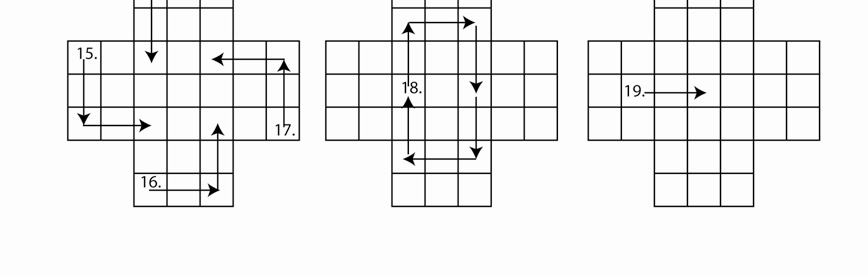

Leibniz gives the following example: “It is very much like what happens in certain games, in which all the spaces on the board have to be filled in according to certain rules: unless you show some ingenuity you will find yourself at the end kept out of certain refractory spaces, and thereby compelled to leave empty more that you need have done, and more than you wished.” (Ultimate, p. 138) – The game Leibniz alludes to here is Solitaire.1

Obviously only possible Solitaire games with a solution, i.e. one peg in the center of the board are candidates for “best possible” solitaire world. Consecutive jumps with one peg are called moves. So a further objective might be to find a solution with as few moves as possible. Whatever the constraints might be the point is that given the solitaire rules, there is a fixed number of possible games and if God wants to realize one of them He must pick out the one that is the best – if there is one.

Since only a complete world is chosen by God it does not make much sense to ask for alternatives within a world. After move 5 in the Dudeney world there must come the move from top left to top right. Otherwise it would be by definition another world.

Leibniz addresses the problem though when he talks of mediate knowledge, that is a knowledge of the possible but not actual. “Instance is given of the famous example of David asking the divine oracle whether the inhabitants of the town of Keilah, where he designed to shut himself in, would deliver him to Saul, supposing that Saul should besiege the town. God answered yes; whereupon David took a different course.” (Theodicy, p. 145)

This example is rather complicated since it asks for the hypothetical reaction of the inhabitants of Keilah to a counterfactual condition. Leibniz thinks he can use the possible world concept to handle it: “For the case of the siege of Keilah forms part of a possible world, which differs from ours only in all that is connected with this hypothesis, and the idea of this possible world represents that which would happen in this case.” (Theodicy, p. 146)

But actually the problem starts with the first step: Will Saul besiege the town or not. Or put in a different way: Are there possible worlds in which Saul besieges the town and others in which he does not? Now, given the principle of sufficient reason this cannot be because it would suppose two possible worlds that are exactly alike until Saul takes an arbitrary decision to siege in world A and not to siege in world B. Since every decision must have a sufficient reason it means that something in world A must have been different from B before Saul makes his decision. Whatever the difference might be, something must have caused this again and so back to the very beginnings of worlds A and B. In other words for two worlds to be different it is necessary that they differ at the start.

This means there can be no “trans-world-identity”. Leibniz, of course, is well aware of this. This is why he speaks of an “approximation” of Sextus when imagining a Sextus who did not rape Lucretia. And about “counterparts” of Adam he says: “When considering Adam we consider a part of his predicates, as for instance that he is the first man, set in a pleasure garden […] and we give the name »Adam« to the person to whom these predicates are attributed, all this is not sufficient to determine the individual, for there might be an infinity of Adams …” (Correspondence, p. 55)

But if there are an infinity of Adams, or of Sauls, by whatever loose criterion, then God’s answer to David’s question could only be something like: Out of the infinity of reasonably “similar” possible worlds the inhabitants of towns similar to Keilah would deliver you in 52% of them.

If only “our” Adam has all the predicates to determine the individual, how can any (description of one) of his actions be called contingent? Or, what comes to the same thing, in what sense can his actions be of free will, if any alternative action would by definition not be his and thus not be one of this world?

For Leibniz in every universal affirmative truth the predicate is in the subject (Specimen, p. 75) or formulated slightly differently the “notion of the predicate is in some way contained in the notion of the subject.” (Primary, p. 87). Every truth can in the end by analysis of its notions be reduced to a primary truth, that is, to an identity like “A is A”. An absolutely necessary truth is one whose opposite implies a contradiction, like truths of mathematics. A truth like “Adam is rational” can be shown to be true since Adam is a man and man is by definition a rational animal. That is, the truth can be resolved to truths of identity in a finite number of steps. These truths are also called metaphysical or geometrical.

A truth of fact on the other hand, or a contingent truth, is one whose contradiction is not impossible. But its truth is just as certain. The essential distinction between necessary and contingent truth - and Leibniz calls this a “wonderful secret” (Primary, p. 88) – is that it takes infinitely many steps to reduce a contingent truth to a primary truth. In the case of contingent truths “the reduction proceeds to and is never terminated. So the certitude and perfect reason of contingent truths is known only to God.” (Speciman, p. 75)

2. Wittgenstein’s Possible Worlds

In the case of Wittgenstein it is less obvious that he had a concept of possible worlds. It is not mentioned in the Tractatus at all and only in passing in the Notebooks where he uses “possible” as an alternative to imagined world. He does not seem to use it as a technical term when says: “In every possible world there is an order even if it is a complicated one.” (NB, p. 83)

In the Tractatus he sometimes seems to speak of world in a metaphorical sense, e.g. in 6.43 (”The world of the happy is quite another than that of the unhappy.”) or in 5.6 (”the limits of my world”).

But in the “ontological” section at the beginning of the Tractatus where he introduces the objects, he says that the objects form the substance of the world (2.021) And he goes on: “It is clear that however different from the real one an imagined world may be, it must have something – a form – in common with the real world.” (2.022) This form consists of the objects. (2.023)

What this suggests is that the World in 2.021 is to be understood as “the totality of possible worlds”.

Although interpretations vary wildly even as to the meaning of the most basic of Wittgenstein’s concepts the ontology of the Tractatus is really quite simple if taken literally.

- 1. All possible worlds share a common substance – simple objects.

- 2. An object can stand in configuration with some others (can be concatenated with them) and together they form a “state of affairs” (or “atomic fact”).

- 3. A state of affairs either exists or not.

- 4. The sum of all existing states of affairs constitutes the (actual) world.

Whatever the nature of an object and whatever the nature of a state of affairs, Wittgenstein is crystal clear about one thing: the objects determine the number of possible states of affairs. Every subset of possible states of affairs (including of course the empty set) can exist. If the states of affairs (in a subset of all states of affairs) do exist they build the actual world, if not, they form a merely possible world.

The sum of existing states of affairs determines the ones that do not exist. That any subset can be seen as a possible world is of course due to the wonderful property of the state of affairs, namely, to be independent of one another. Wittgenstein says so explicitly in 2.061: “States of affairs are independent of one another.” And more prominently right at the beginning: “Each item can be the case or not the case while everything else remains the same.” (1.21)

The independence thesis has never been very popular, perhaps because it seems to be just as implausible as the claim that this is the best of all possible worlds. Raymond Bradley calls it the “myth of independence”. (Bradley, p. 101)

Attempts have been made to make sense of the thesis, the most obvious one by distinguishing a logical from an ontological independence. Bradley provides the rather lukewarm solution that only “entirely different” states of affairs are independent. (Bradley, p. 120)

A strict reading of the Tractatus is not made easier by the well-known fact that Wittgenstein himself had later some serious doubts about the truth of some of the main assumptions of the Tractatus.

But on the positive side, I for one, find it rather difficult to resist the charm of the Tractatus, where it says, that given a fixed form (the objects) that can combine to n states of affairs, all possible worlds can be established. If there are n possible states of affairs there are 2n combinations of states of affairs (4.27) and thus 2n possible worlds. And since there is a one-to-one relationship between states of affairs and elementary propositions, I can take any logical product of elementary propositions to describe a possible world. The truth of an elementary proposition does only depend on the existence of the depicted state of affairs. So while it takes an infinite number of steps to prove the truth of a contingent proposition according to Leibniz, the truth (or falsity) of an elementary proposition is immediately given. (Of course, how to analyze a sentence of ordinary language like “the watch lies on the table” is quite a different question.)

If we have two states of affairs a and b we obviously have four possible worlds, the empty one, the one where a exists, the one where b exists and the one where a and b exist. We can visualize them like this: [a], [b], [ ], [ab]. We might call them A, B, C, D respectively. Let p be the proposition that says that a and q be the proposition that states b, then p is true in A (or A is a truth-maker of p) and in D. Instead of saying that p is true in two possible worlds one could take it one step further and say that p is made true by the set of possible worlds consisting of A and D. In this way any logical combination of the two elementary propositions is made true by one of the 16 sets of combinations of possible worlds. The tautology if p then p and if q then q is made true by {[A], [B], [C], [D]} the contradiction by {[ ]}. Instead of using logical constants or truth tables we could take any number of elementary propositions and point to one set of sets of possible worlds that is a truth-maker of any logical connection between them.

3. Conclusion

We have seen that Leibniz and Wittgenstein are at opposite ends with regard to the ontological status of the world and to the logical status of a contingent truth. For Leibniz every tiny piece of the world is essentially connected to every other: “For it must be known that all things are connected in each one of the possible worlds: the universe, whatever it may be, is all of one piece, like an ocean: the least movement extends its effect there to any distance whatsoever, even though this effect become less perceptible in proportion to the distance.” (Theodicy, p. 128) To understand one contingent sentence, you must fully understand the whole universe.

So because of the interconnectivity only on the level of complete worlds there is a form of independence.

With Wittgenstein, on the other hand, we have total compossibility on the level of the states of affairs. Instead of an ocean his world resembles a jigsaw puzzle. Any piece might be missing, we still have a complete picture of the world. A missing piece does not affect the other pieces at all. We can totally understand a contingent proposition without knowing anything about the rest of the world.

The price to pay is rather high for both of them. Accepting Leibniz’ view means to accept a world that is fully determined. Accepting Wittgenstein means one has to be totally agnostic as to the question how an ordinary sentence is analyzed, what is the nature of an object. One can only say that all attached properties to objects must somehow emerge from a concatenation of real objects, including colour and a position in space and time.

Illustration

Fig. 1: Best of all possible Solitaire worlds? Henry Ernest Dudeney's elegant 19-move solution.

Fig. 1: Best of all possible Solitaire worlds? Henry Ernest Dudeney's elegant 19-move solution.Literature

- Bradley, R. 1992 The Nature of All Being, Oxford: Oxford Univerity Press.

- Berlekamp E.R., Conway, J. and Guy, R.K. 1982 Winning Ways for Your Mathematical Plays, Vol.2 Games in Particular London: Academic Press.

- Gerhardt, C.I. (ed.) 1965 Die Philosphischen Schriften von Leibniz, 7 vols. Berlin: Weidmann, 1875-90; reprinted Hildesheim: Olms.

- Leibniz, G.W. Theodicy: Essays on the Goodness of God, the Freedom of Man and the Origin of Evil, Project Gutenberg. Translated by E.M. Huggard from C.J. Gerhardt's Edition of the Collected Philosophical Works, 1875-90 Access: http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17147/17147-h/17147-h.htm#page123

- Leibniz, G.W. “A Specimen of Discoveries About Marvellous Secrets of a General Nature” in: Parkinson, 1973.

- ––– “Correspondence with Arnauld” in: Parkinson, 1973.

- ––– “Primary Truths” in: Parkinson, 1973.

- ––– “On the Ultimate Origination of Things” in: Parkinson, 1973.

- ––– “Über die ersten Wahrheiten” in: Holz, H.H. (trans. and ed.) 1973 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz: Kleine Schriften zur Metaphysik Frankfurt am Main: Insel.

- Mates, B. “Leibniz on Possible Worlds” in: Frankfurt, H.G. (ed.) 1976 Leibniz: a Collection of Critical Essays London: University of Notre Dame Press.

- Parkinson, G.H.R. 1973 (trans. and ed.) Leibniz: Philosphical Writings, London: Dent.

- ––– “Philosophy and logic”, in: Jolley, N. (ed.) 1995 The Cambridge Companion to Leibniz, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Refbacks

- There are currently no refbacks.